Is God Dead? Part 1

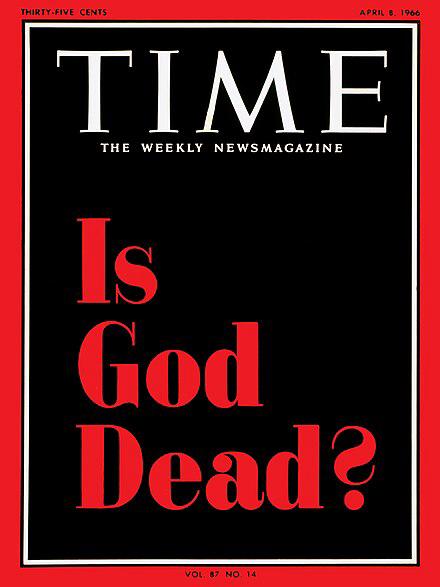

Time Magazine's Provocative Cover

“IS GOD DEAD?” asked Time magazine in its April 8, 1966 issue. Yes, “God is dead,” responded three American theologians: Thomas Altizer of Emory University in Atlanta, William Hamilton of Colgate-Rochester Divinity School, and Paul Van Buren of Temple University. This bold response to a very extraordinary question proved to be the birth of what is known as “The Death of God” school, a movement marking one culmination of a centuries-old study into the origin, existence, nature, and relevance of the “Transcendent God” of theism.

This famous cover reflected a period of profound questioning and change in the religious landscape of the United States and the Western world regarding the Christian, medieval concept of an absolutist, authoritarian, intrusive, omniscient, and anthropomorphic God. The article inside discussed the growing trend of secularism and the decline of traditional religious belief among a large segment of the population, especially in the context of modern religious, philosophical and theological thought. However, the magazine's approach was more journalistic, focusing on contemporary trends in theology and society's changing relationship with religion. This cover story sparked widespread debate and discussion about the role of religion in modern society.

Based on that provocative analysis and the ensuing unending debates, the coming posts will examine the claimed origins of religion (modern theories of origins of religion) and the rise of man creating God in his own manlike (anthropomorphic) image: its ancient connotations, its historical development down the centuries, and what it has meant to followers of different faiths, as well as to philosophers, scholars, and theologians. Also examined will be the various levels of criticism directed towards its (manlike attributes) application to God, where it collides with corporealism, incarnation, and mystical interpretation, and where it has been considered appropriate to use about ‘knowing’ God, strictly qualified of course and hemmed in by carefully defined parameters.

Posts' Scheme

It will be shown during these posts that modern critical scholars have primarily examined and analyzed the biblical portrayal of an evolving, progressive, dynamic, and manlike God which contrasts sharply with the Islamic view of God as singular, otherworldly, unique, transcendent, morally upright, and logical. This trend highlights an irony: the fluid Western viewpoint on divinity, scripture, and religion is often inappropriately projected onto Islam, disregarding its distinct theological foundations, straightforward linear scriptural history, and a strict, well-structured, and, well-guarded universal concept of God that rejects human-like physical descriptions, human limitations and moral flaws. This situation reveals a troubling truth: Western thought, influenced by Eurocentrism and notions of supremacy, often positions itself as the center of global discourse. This leads to the evaluation of other cultures through a distorted perspective, neglecting the rich historical, religious, and philosophical backgrounds of these cultures and instead imposing a narrow European narrative on worldwide phenomena without proper scholarly objectivity.

Western Context

Within the Western context in general and the Christian context in particular, the confident-sounding claims concerning the death of God are neither unusual nor are they new. For centuries, philosophers, intellectuals, and scientists have viewed the theistic conception of God as too confusing, complicated, and indeed inconsequential, arguing that the idea of a transcendental God and his authoritative institutions have become irrelevant to man and his surroundings. This postulation is implied in many philosophical and scientific writings.

Friedrich Nietzsche

In the relatively modern age, to speak of “the death of God” is to invoke the name of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844– 1900), a famed German philosopher and nihilist, who stated these very words at the end of the nineteenth century. Nietzsche used this phrase to express the idea that the European Enlightenment had "killed" the possibility of God's existence or at least the belief in God and his role in society, as science and rationality replaced faith and the supernatural. The Enlightenment not only rejected Christianity and its medieval irrational dogmas and persecutory church but intellectually killed the God who sanctioned them. Modernity has diminished the need for and reliance on religion and it’s God.

Writing on the various stages of development that ultimately led man – in Europe anyway – to the shared cultural belief that God was dead, Nietzsche first pointed to the many gods (polytheism) worshipped by ancient humanity. These in turn gave way to the jealous, biblical God of the Old Testament who declares, “There is but one God! Thou shalt have no other gods before me!” All the other gods, wrote Nietzsche, then laughed and shook upon their thrones, exclaiming an interesting secret: “Is it not just divinity that there are Gods, but no God?” expiring from their laughter.

The multiple deities of ancient times, according to Nietzsche, connected usefully with human needs or natural forces. The one God who replaced them, however, transcended human will and was too intrusive, disturbing, and involved in human affairs. This God, wrote Nietzsche “beheld everything I use, and also man: that God had to die! Man cannot endure that such a witness should live.”

Death of God Meanings

This (manlike God and his ultimate death) concept has been widely debated and discussed in philosophical, theological, and cultural contexts. It's not a literal question about the physical existence of a deity, but rather a metaphorical exploration of the role of religion and spirituality in a modern, rational world. Commenting on Nietzsche’s observations, religious ethics scholar Paul Ramsey explains that the religious conception of an omnipresent God (mostly Western Christian concept of God) “was too much God with us, God in human, all-too-human form. He mixed too much in human affairs, even manifesting himself in this miserable flesh. In a sense, God’s fellow humanity killed him.” Furthermore, “After the gods made in man’s image, the God who proposed to make and remake man in his own image, that God too had to die.”

So, this “death of God” solution was necessary to liberate man from the unlimited restrictions, or so-called religious, un-scientific interpretations of man, his institutions, and the universe, imposed in the name of God upon the scientific and cultural products of men. This death wrote German-Jewish philosopher Karl Löwith, “demands of the man who wills himself, to whom no God says what he must do, that he transcends man at the same time as he is freed from God.”

This view considered men as autonomous and unlimited creators of their culture and destiny without any religious supervision or interference. Whereas in the past humanity, due to ignorance, would accomplish this task by projecting its fears and aspirations into the cosmos through the creation of gods, now it achieves this autonomy through education, science, technology, and philosophy. In other words, science, technology, and rationalism have effectively killed God removing the need for Him in the development of human culture and activity. So important is this line of thought that it is the belief of James C. Livingston, a scholar of modern religious thought, that the outcome of this development has been “the death of the ultimate ground and support of all traditional values. For over two thousand years men have derived their ‘thou shalt’ and ‘thou shalt not’ from God, but that is now coming to an end.”

A Long Tradition

In poetic and prophetic terms, Nietzsche meant to represent the numerous critics of a theistic understanding of God, who for many centuries had asserted that the traditional, official, and transcendent God of theism had lost authority over the world and His usefulness to it. “In man, the consciousness of an ultimate in the traditional sense has died.” This means that the God who was once worshipped as the Creator of the universe, the giver of law, and the source of cosmic meaning was no longer accepted in that role and was no longer seen as the Creator of humanity, the world, or the cosmos. Ironically, it was now humanity itself that shaped God in its own image. In ancient times, humans conceived of God as having a physical body, organs, human emotions, actions, and attitudes, projecting their fears onto the cosmos. However, modern science and knowledge have dispelled those fears and anxieties. As a result, the need for that invented, projected and fabricated God has faded away.

Projection Theories of Religion

Projection theories or claims concerning the human origins of notions relating to the divine are not recent. They can be traced back to the Greek philosopher-poet Xenophanes (570–470 BC), around six hundred years before Jesus Christ. Criticizing the anthropomorphism of Homer and Hesiod in their portrayal of gods, Xenophanes wrote: “if oxen (and horses) and lions...could draw with hands and create works of art like those made by men, horses would draw pictures of gods like horses, and oxen of gods like oxen...Aethiopians have gods with snub noses and black hair, Thracians have gods with gray eyes and red hair.”

Xenophanes's Theory and Jesus

The medieval and contemporary Christian tendency to depict differing portrayals of Jesus substantiates Xenophanes's theory of projection. Different cultures often depict Jesus in ways that reflect their own racial and ethnic features. This phenomenon is known as the inculturation of religious figures, where a culture adapts religious icons in its own image.

Western Portrayals: In Western art, particularly from the European Renaissance onwards, Jesus is often depicted with fair skin, blue eyes, and light brown or blond hair. This portrayal reflects the predominant characteristics of people in those regions.

African Interpretations: In African cultures, Jesus is frequently depicted with darker skin, black curly hair, and African facial features. This reflects the desire to see Jesus as part of their culture, embodying characteristics familiar to African people.

Asian Depictions: In countries like China and Korea, artistic renditions of Jesus might show him with Asian features, such as a flatter face, a snubbed nose, and smaller eyes. This localization makes Jesus more relatable to the people in these regions.

Historical Reality: Historically, as a Palestinian Jew of his time, Jesus likely had olive-brown skin, black hair, and a medium build, reflecting the typical physical characteristics of Middle Eastern people of that era.

Each culture's representation of Jesus is an expression of their desire to see the divine in a form that is familiar and relatable to them. They project their image into the clouds and see their self-image, though refined, God (Jesus) in the heavens. These diverse images, while underscoring the universal appeal of Jesus' message across different cultures and ethnicities, also highlight the reality that people tend to project their aspirations, fears, anxieties, and features into the celestial realms.

Human Projections of Fears

It has long been claimed that the origins of religion and the worship of gods has stemmed from man’s inner desires as well as attempts to explain and control the natural environment around him, particularly its disturbing and puzzling phenomena. In the words of Cicero, “In this medley of conflicting opinions, one thing is certain. Though it is possible that they are all of them false, it is impossible that more than one of them is true.” The “Awe,” according to Cicero, evoked in man by terrifying natural phenomena and attempts to comprehend a greater power, was pivotal in helping to produce conflicting religious opinions and images of the divine.

Francis Bacon

Writing in the fifteenth century, Francis Bacon (1561–1626), virtually substantiated Cicero’s observations by noting that human understanding relied upon causes that related “clearly to the nature of man rather than to the nature of the universe.” These significant observations were hallmarks of a new era: the era of science. Bacon, regarded by many as the leading philosopher of modern science and a prophet of empiricism, maintained that man anthropomorphizes. Under the now famous heading “idols and false notions” he classified anthropomorphism into four separate kinds: idols of the tribe, cave, marketplace, and theater. Bacon believed that tribal idols were based on the false assumption that the sense of man is the measure of things. On [the] contrary, all perceptions as well of the sense as of the mind are according to the measure of the individual and not according to the measure of the universe. And human understanding is like a false mirror, which, receiving rays irregularly, distorts and discolors the nature of things by mingling its own nature with it.

Bacon held that human perceptions depend on and are motivated by human feelings. He pinpointed to the human tendency to anthropomorphize as a fundamental weakness of the human thought process, and its major stumbling block.

Bernard Fontenelle

In the sixteenth century, French writer Bernard Fontenelle (1657– 1757), renewed the old Cicerian approach by proposing a universal evolutionary framework for the development of human thought and culture. Fontenelle believed that even the most ancient and crude centuries had had their philosophers. And these ancient philosophers had used the same anthropomorphic method as ours to explain the unseen and unknown by recourse to the seen and known, though they had used crude images and metaphors vastly different from our sophisticated technological symbols and images.

Fontenelle stated, “This philosophy of the first centuries revolved on a principle so natural that even today our philosophy has none other…we explain... unknown natural things by those which we have before our eyes, and that we carry over to natural science...those things furnished us by experience.” Natural forces beyond human control lead people to imagine beings that are more powerful than themselves, able to significantly affect human lives and destinies. Furthermore, the very diversity of natural forces explains the multitude of primitive divinities worshipped, these gods the products of human thought and circumstances being thus anthropomorphic.

Therefore, the nature as well as qualities and attributes of these gods, change accordingly with changes in human thought patterns and culture. Primitive people ascribed rudimentary attributes to their gods i.e. physical bodies, corporeal attributes, and crude anthropomorphic qualities. The more educated and sophisticated groups likewise described their gods in more developed forms and categories i.e. love, compassion, spiritual existence, and transcendentalism. Hence, the conception of a god or gods in any given society reflected that society’s culture and sophistication.

Benedict de Spinoza

Seventeenth-century philosopher Benedict de Spinoza (1632–1677) followed Bacon in criticizing the human tendency of anthropocentrism (regarding humankind as the central or most important element of existence, especially as opposed to God or animals) and anthropomorphism (the interpretation of nonhuman things or events in terms of human characteristics). He regarded our perceptions of the world as extending from our views regarding ourselves. As we do things for certain ends, we perceive nature working for specific ends. Yet when humans “cannot learn such causes from external causes,” Spinoza wrote, “they are compelled to turn to considering themselves, and reflecting what end would have induced them personally to bring about the given event, and thus they necessarily judge other natures by their own.” Therefore, gods and other transcendental beings are simply mere creations of human imagination. They are seen to exist only in the imaginative world of man.

David Hume

David Hume (1711–1776), Scottish philosopher and economist, pioneered this line of approach in the modern age. He provided a more detailed account of the anthropomorphic nature of the divine. According to his thinking, notions about the divine did not spring from reason but from the natural uncertainties of life and out of fear of the future. The resulting invented divine entity provided man with a framework of meaning boosting his confidence against uncertainty-related anxieties and concerns for happiness. As a result, man was allowed to feel an artificial sense of orderliness, peace, and security in a world full of disorderliness and insecurities.

Viewing the idea of God in evolutionary terms, Hume rejected the theory of an original monotheism and considered the earliest form of religion to be idolatry or polytheism; the origin of the idea of God resulted as man personified his hopes and fears into the cosmos, then worshipped gods created in his own image. After placing the world of ideas in the realm of human experience and impressions, Hume argued that even refined and abstract ideas of the divine or God sprang only from human senses and experiences.

Man’s worries about the uncertainties of the future included the anxious concern for happiness, the dread of future misery, the terror of death, the thirst for revenge, the appetite for food, and other necessities. Agitated by hopes and fears of this nature, especially the latter, men scrutinize, with trembling curiosity, the course of future causes, and examine the various and contrary events of human life.

This sheer anxiety leads humanity to imagine and formulate ideas about powers governing them: “These unknown causes, then, become the constant object of our hope and fear; and while the passions are kept in perpetual alarm by an anxious expectation of the events, the imagination is equally employed in forming ideas of those powers, on which we have so entire a dependence.” This anthropomorphic tendency of modeling all unknown powers after familiar human categories is the foundational source of man’s belief in the divine. Neither is it limited to primitive man but is also the case for modern believers who like their ancestors, harbor the same tendencies. “Ask any contemporary believer why he believes in an omnipotent creator of the world; he will never mention the beauty of final causes, of which he is wholly ignorant: He will not hold out his hand, and bid you contemplate the suppleness and variety of joints in his fingers, their bending all one way...To these he has been long accustomed, and he beholds them with listlessness and unconcern. He will tell you of the sudden and unexpected death of such a one: The fall and bruise of such another: The excessive drought of this season: The cold and rains of another. This he ascribes to the immediate operation of providence: And such events, as, with good reasoners, are the chief difficulties in admitting a supreme intelligence, are with him the sole arguments for it.”

David Hume placed this anthropomorphic, projection principle that originated with Xenophanes in a systematically coherent epistemological context. His analysis guides and serves as a point of reference for many modern scholars of religious philosophy and sociology who share his assumptions: Auguste Comte, Ludwig Feuerbach, Edward Tylor, Sigmund Freud, Thomas De Quincy, Robert Browning, Matthew Arnold, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Emily Brontë, Jean-Paul Sartre, Maurice Merleau Ponty, Albert Camus, A.J. Ayer, and E. D. Klemke, for example. Auguste Marie Francois Comte (1798–1857), the father of modern sociology, rejected like Hume and other modern philosophers and idealists, transcendental metaphysics and theology.

Emphasizing the intimate relationship that existed between ideas and society and the evolutionary nature of human thought, Comte applied his Law of the Three Stages (theological, metaphysical, and positive related to societal development) to human religious thought: the theological-military, the metaphysical-feudal, and the positive-industrial. Comte located the idea of the divine in the first and primitive stage (theological) of mankind. He further subdivided this age into three main periods, i.e.: fetichism, polytheism, and monotheism. The first stage “allowed free exercise to that tendency of our nature by which man conceives of all external bodies as animated by a life analogous to his own, with difference of mere intensity.”

Its motive, as Hume already observed, was to try to apprehend and make some sense of unknown effects. After the idea originated in the anthropomorphic nature of mankind, it developed into polytheism, passing through the Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Judaic cultures, to reach the third stage to become modified into monotheism.

To be continued.

For details see my book “Concept of God in the Judeo-Christian and Islamic Traditions”, chapter 1

Related Articles

The emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE with a distinct, democratically oriented, consultative governmental structure

Dr. Zulfiqar Ali Shah, Even though the central pivot of all New Testament writings is Jesus Christ and crucial information...

Gaza City, home to over 2.2 million residents, has become a ghostly emblem of devastation and violence

Gaza City, a sprawling city of over 2.2 million people is now a spectral vestige of horrors

The Holy Bible, a sacred text revered by Jews and Christians alike, has undergone centuries of acceptance as the verbatim Word of God

Tamar, the only daughter of King David was raped by her half-brother. King David was at a loss to protect or give her much-needed justice. This is a biblical tale of complex turns and twists and leaves many questions unanswered.

There is no conflict between reason and revelation in Islam.

The Bible is considered holy by many and X-rated by others. It is a mixture of facts and fiction, some of them quite sexually violent and promiscuous. The irony is that these hedonistic passages are presented as the word of God verbatim with serious moral implications.