Muslims and St. Thomas Aquinas

St. Thomas aimed his writings primarily at Muslims, seeking to convert them through his philosophical theology. Jews, Christians, and pagans were considered secondary audiences. His major works, the Summa Contra Gentiles and the Summa Theologica, were both directed towards engaging with Muslims. Alfred Guillaume observes that “The Summa contra Gentiles possesses such enormous value in itself that the primary object of its composition has been lost sight of. Yet the connexion between it and Islam is indissoluble. It was written at the request of the Master-General of the Dominicans, Raymund of Pinnaforte, with the express purpose of convincing the Muslims of Spain of the rational basis of Christianity and the errors of their own religion. In the second chapter of the Summa (quae sit auctoris intentio) St. Thomas particularly singles out Muhammadans. Jews, he says, can be refuted from the Old Testament; heretics from the New Testament; but Machomestitae et Pagani can only be convinced by natural reason. And it is to natural reason that he proceeds to appeal.”

Thomas and Prophet Muhammad

St. Thomas made several references to Prophet Muhammad and Muslims in his Summa. Guillaume notes that “The first is in I, vi. Here St. Thomas shows that he is acquainted with the Quran (ut patet eius legem inspicienti). Presumably his knowledge of it was gained from the version which was completed in 1143. It was a translation in Latin made by "Robertus Retinensis, an Englishman, with the assistance of Hermannus Dalmata, at the request of Peter, abbot of Clugny". St. Thomas makes two important points, one explicit, the other implicit. Muhammad, he says, produced no miracle in support of his claim to be the apostle of God (signa etiam non adhibuit supernaturaliter facta) and, to remove in advance Muhammad's claim (of which he seems to be aware) that the Quran itself is a miraculous proof of his divine mission, he prefaces this statement by the words Documenta etiam veritatis non attulit nisi quae de facili a quolibet mediocriter sapiente, naturali ingenio, cognosci possint.”

Thomas and Muslim Scholars

St. Thomas distinguished himself from his Christian contemporaries by openly engaging with Muslim and Jewish scholars. He frequently cited Muslim theologians and philosophers, albeit usually acknowledging them by name only to challenge their views, while often omitting their influence when he agreed with or borrowed from their ideas. Despite this approach, St. Thomas's work was deeply influenced by Islamic thinkers. His engagement with their works was not superficial but a profound interaction, where he both opposed and absorbed their concepts. He was particularly influenced by the works he accessed through Rabbi Moses Maimonides, a prominent figure in bridging Islamic and Christian thought. The impact of Muslim scholarship on St. Thomas was significant, extending to the adoption of their ideas, vocabulary, structure, methods, and even their intellectual strategies, to the point where some aspects of his work closely mirrored those of his Muslim predecessors. This deep immersion in Muslim thought was integral to St. Thomas's unique synthesis of Christian theology, indicating that Islamic philosophy and theology played a crucial role in shaping his intellectual landscape. He “moved in the same circle of ideas as his would-be converts.”

David B. Burrell, the world authority on St. Thomas, depicts St. Thomas as an interfaith figure, who liberally interacted with the Jewish and Islamic theologico-philosophical thought. He observes that “The work of Thomas Aquinas may be distinguished from that of many of his contemporaries by his attention to the writings of Moses Maimonides (1135–1204), a Jew, and Ibn Sina [Avicenna] (1980–1037), a Muslim…So while Aquinas would consult “the commentator” [Averroës] on matters of interpretation of the texts of Aristotle, that very aphorism suggests the limits of his reliance on the philosophical writings of Averroës, the qadi from Cordova. With Maimonides and Avicenna his relationship was more akin to that among interlocutors, especially so with “Rabbi Moses”, whose extended dialectical conversations with his student Joseph in his Guide of the Perplexed closely matched Aquinas’ own project; that of using philosophical inquiry to articulate one’s received faith, and in the process extending the horizons of that inquiry to include topics unsuspected by those bereft of divine revelation.”

The Dominant Islamic Culture

It's important to recognize that Maimonides, along with many medieval Jewish philosophers and theologians, was significantly shaped by Islamic culture and civilization. Indeed, the intellectual contributions of these Jewish scholars often mirrored the dominant cultural and intellectual milieu of the Muslim civilization during the Middle Ages. The forthcoming discussion will further explore how Islamic civilization, as the prevailing cultural force of the time, profoundly influenced the development and perspectives of medieval Jewish thought. This influence underscores the interconnectedness of these cultural and intellectual traditions, highlighting the role of Islamic civilization in shaping a significant portion of medieval scholarly work.

Burrell observes that “it is worth speculating whether the perspective of Aquinas and his contemporaries was not less Eurocentric than our own. What we call “the west” was indeed geopolitically surrounded by Islam, which sat astride the lucrative trade routes to “the east”. Moreover, the cultural heritage embodied in notable achievements in medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and well as the logical, philosophical commentary, translation, and original work in metaphysics begun in tenth-century Baghdad, represented a legacy coveted by western medieval thinkers. Marshall Hodgson has called the culture that informed this epoch and extended from India to Andalusia “the Islamicate”, intending thereby to include within its scope Jewish thinkers like Maimonides who enjoyed the protected status of dhimmi and contributed to Muslim civilisation. Christians like John of Damascus enjoyed a similar status, reserved by Qur’anic authority for “people of the book”, yet the divisions in Christendom saw to it that thinkers in Paris were better acquainted with Muslim and Jewish thinkers than with their co-religionist in Islamic regions.”

Role of Southern Italy

Burrell also notes that St. Thomas’s upbringing in Southern Italy, and his geographical and intellectual affinity with the Islamic culture and civilisation, played a role in his intellectual development. “Aquinas’ own geographic and social origins could well have predisposed him to a closer relationship with thinkers representative of the Islamicate than his contemporaries could be presumed to have had, in Paris at least. For his provenance from Aquino in the region of Naples, itself part of the kingdom of Sicily, reflected a face of Europe turned to the Islamicate, as evidenced in the first translations commissioned from Arabic: “Latin, Muslim, and Jewish culture mingled freely in Sicily in a unique way that was peculiarly Sicilian.” Moreover, in his later years, when his Dominican province asked him to direct a theological studium, Aquinas expressly chose Naples (over Rome or Orvieto) for its location, and that for intellectual reasons; “there was a vitality about Naples that was absent from Rome or any other city in the Roman province”. So it might be surmised that these dimensions of his own personal history led him to be more open to thinkers from the Islamicate than his co-workers from Cologne or Paris might have been. In any case, the number and centrality of the citations from Avicenna and Moses Maimonides leave no doubt as to their place in his intellectual development.” St. Thomas’s interfaith approach to theology was unique for his times and valuable for the coming generations.

Role of Crusades

The life and work of St. Thomas Aquinas were deeply intertwined with the presence and influence of Islam, the Muslim world, and the Crusades to the Holy Lands. His upbringing in Southern Italy, positioned near countries with significant Muslim populations, and Latin Christendom's complex relationships with these regions, imbued his intellectual and vocational pursuits with a focus on Islam-related subjects from an early age. Understanding personalities like Aquinas requires acknowledging the historical context that shapes their development and perspectives. In the thirteenth century, Italy, France, and Spain were deeply engaged with Muslim politics, missions, religion, philosophy, culture, and conflicts, making Muslims an integral aspect of Aquinas's environment and concerns.

Thirteenth Century Upheavals

The thirteenth century was a period of dramatic shifts and upheavals, marked by radical changes and often violent conflicts that left a lasting impact on history. Although it's challenging to capture the full dynamics of this era briefly, it's crucial to note that the Crusades were among the defining features of thirteenth-century Christendom. Compared to the culturally advanced Muslim world, Christendom, smaller and less developed, engaged in a series of Crusades from 1095, with Aquinas's lifetime witnessing an unprecedented crusading zeal. This period saw five Crusades (from the fourth to the ninth) between 1200 and 1272, led by various Christian leaders from across Europe. The Crusades, with Rome at their heart and stretching across the continent, especially France, were central to the Christianizing mission of the time.

King Louis IX of France

King Louis IX of France played a pivotal role in this mission, exemplifying the Christian king and leading the charge for Christianization, both within Europe and globally. The merging of Church and state under this mission saw the pooling of resources towards a spiritual revolution aimed at establishing the Kingdom of God on Earth, in line with Christ's teachings. The Mendicant Orders, particularly the Franciscans and Dominicans, were crucial to this vision, spreading Christianity through their network of convents, schools, and disciplined friars.

Crusades and Christianization

The Crusades, targeting both Christian and Muslim territories, were the most visible sign of this Christianization effort, with the Holy Land and Jerusalem as the ultimate goals. Efforts to unify Christendom against its perceived enemies, including Muslims and internal heretics, were intensified after the re-conquest of Jerusalem by Saladin in 1187. This period, marked by a feverish crusading spirit with King Louis IX at the forefront, highlights the complex and often contentious interactions between the Christian and Muslim worlds during Aquinas's time.

Since the eleventh century, there was ongoing interaction between the Latin World and the Crusader States of the Holy Land, with Franciscans, Dominicans, soldiers, and diplomats regularly traveling across the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily, Spain, and the cultural, educational, and political hubs of Latin Europe. This exchange intensified in the 1240s as King Louis IX prepared for his Seventh Crusade in 1248, leading to widespread crusade preaching across France, Germany, Italy, and Spain. This campaign involved a broad spectrum of society, including papal legates, mendicant friars, secular clergy, volunteer preachers, and government officials. Popes mobilized the Christian faithful across Europe through general letters or bulls, which served as powerful propaganda tools, outlining crusade motivations, themes for preachers, and the privileges granted to participants. The Latin Christian community was thus fully engaged with the crusades, informed by papal decrees, ecumenical council decisions, and recruitment campaigns, often framing Islam and Muslims in starkly negative terms as the feared and vilified "other."

For many participants, the crusades were akin to a pilgrimage, leading to an increased understanding of the Muslim East, sometimes even resulting in conversions to Islam. These experiences allowed crusaders to view Christendom's societal and religious challenges through the lens of Muslim culture. Moreover, interactions with Eastern Christians broadened their perspectives, enhancing religious, economic, and cultural connections across the Afro-Eurasian supercontinent. This era of European expansion, coupled with the flourishing of trade and cultural exchanges with Muslims, Byzantines, and Mongols, marked a period of unprecedented global connectivity.

However, the numerous failures and moral controversies surrounding the Crusades also prompted significant Christian introspection and theological dilemmas. Throughout his life, from Aquino to Naples, Paris, and Rome, Thomas Aquinas was immersed in these debates and cultural exchanges. The Crusades, along with their intellectual and cultural repercussions, deeply influenced Aquinas's thought and work. His life was marked by the influence of figures such as King Louis IX and Popes Urban IV, Clement IV, and Gregory X, who were deeply involved in the Crusades and were significant patrons of Aquinas and the Dominican Order. The realities of the Crusades and the central role of Islam and Muslims within them positioned Aquinas at the intersection of competing religious and philosophical ideologies, necessitating thoughtful engagement, adaptation, and defense of his beliefs.

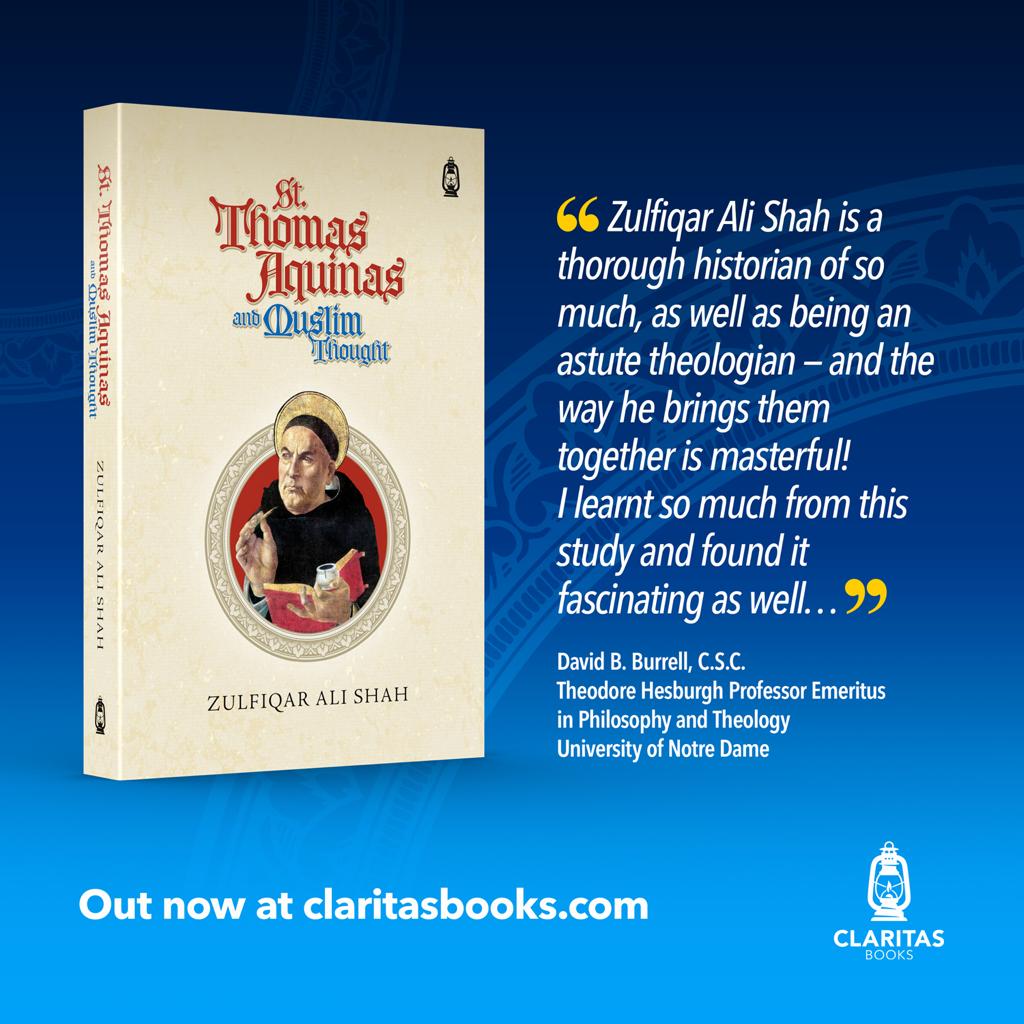

See details in my book "St. Thomas Aquinas and Muslim Thought."

Related Articles

The emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE with a distinct, democratically oriented, consultative governmental structure

Dr. Zulfiqar Ali Shah, Even though the central pivot of all New Testament writings is Jesus Christ and crucial information...

Gaza City, home to over 2.2 million residents, has become a ghostly emblem of devastation and violence

Gaza City, a sprawling city of over 2.2 million people is now a spectral vestige of horrors

The Holy Bible, a sacred text revered by Jews and Christians alike, has undergone centuries of acceptance as the verbatim Word of God

Tamar, the only daughter of King David was raped by her half-brother. King David was at a loss to protect or give her much-needed justice. This is a biblical tale of complex turns and twists and leaves many questions unanswered.

There is no conflict between reason and revelation in Islam.

The Bible is considered holy by many and X-rated by others. It is a mixture of facts and fiction, some of them quite sexually violent and promiscuous. The irony is that these hedonistic passages are presented as the word of God verbatim with serious moral implications.