Was The Quran Written 200 Years After Prophet Muhammad?

Abstract

John Wansbrough speculated that the Qur'an did not exist until the late second century, using a literary method of biblical criticism to analyze its text. He identified elements like divine retribution and covenant in the Qur'an, suggesting its style was "referential" and linked to Judeo-Christian themes. However, his hypothesis overlooks extensive scholarly work on the Qur'an's formation and its unique aspects compared to the Bible. Critics like R.W. Bulliet argue against Wansbrough's views, highlighting the improbability of such a widespread and cohesive religious tradition being based on a fantasy. Patricia Crone and Michael Cook's similar theories have been widely dismissed. The Qur'an's preservation, including discoveries like the Sana'a Manuscripts, challenges Wansbrough's claims, with orthodox Muslims considering its preservation a divine miracle.

John Wansbrough's Speculations

John Wansbrough, who served as a Reader in Arabic at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London until his passing in 2002, authored two contentious works critically examining the Qur’an. He posited that the Qur’an did not exist during Prophet Muhammad's lifetime or even until the end of the second/eighth century. Wansbrough's hypothesis, largely speculative, overlooks extensive scholarly research on the Qur’an’s formation, chronology, textual variations, and its relation to prior literature, as noted by Professor Charles Adam.

Contradicting established perspectives of both Islamic and Western scholars, Wansbrough's approach, as Andrew Rippin observed, suggests that the study of these aspects is still in its infancy. Wansbrough employed a 'literary' method of biblical criticism, similar to Geza Vermes and Raphael Loewe’s analysis of the Bible, conducting a form-critical examination of the Qur’anic text. He identified four primary elements in the Qur’anic message: divine retribution, sign, exile, and covenant, all derived from traditional monotheistic themes, noting their frequent mention but limited development in the text. This led him to describe the Qur’an’s style as "referential," implying that it assumes the audience's knowledge to fill in narrative details, exemplified by the story of Prophet Joseph in Surah 12:59. Wansbrough argued that the Qur’an’s referential nature indicates it is not exclusively Arabian and cannot be detached from its Judeo-Christian context, seeing it as a product of intense Judeo-Christian sectarian discourse, a composite of various traditions.

Judeo-Christian Background

This perspective on the Qur’an’s Judeo-Christian background is not new and has been echoed by several Western scholars such as J. Wellhausen, R. Bell, Tor Andrae, and S. Zwemer. Some, like Wellhausen, Bell, Andrae, and Ahrens, have suggested a Christian Aramaic influence on the Qur’an, while others like H. Hirschfeld, D. Kuenstlinger, and A. Geiger have highlighted its Judaic roots. For instance, Anderson argued that the detailed accounts of Jewish patriarchs in the Qur’an closely align with the Talmud, suggesting a predominantly Jewish origin. Geiger posited that Muhammad incorporated much from Jewish traditions, often blurring the lines between sacred texts, later additions, and exegetical commentary.

Wansbrough's perspective stands in contrast to the generally accepted view of the Qur'an's authenticity and preservation, a stance shared by numerous Islamic and Western scholars. For instance, Bell recognized that “Of any intimate knowledge for the Prophet of either [of] these two religions or the Bible itself there is no convincing evidence.” Additionally, two-thirds of the Qur’an was revealed in Makkah where the Jewish and Christian presence was almost zero. J. Fueck observes that “There is no evidence for the existence of a strong Jewish colony with a living tradition at Mecca, nor does [the] Qur’an give evidence of that intimate knowledge of Jewish matters which we would expect if Muhammad had actually been dependent on Judaism.”

Ahrens portrayed the Prophet as a gang leader and argued that Muhammad “during the greater part of the Meccan period...was predominantly dependent upon Christians in the formulation of his doctrines.” He also claimed that Muhammad compromised the best of those principles that had been drawn from Christianity because of political opportunism. Johann W. Fück (Fueck) (1894–1974), a German orientalist, refuting these allegations, argues: “How, we ask, is it possible for a gang leader who supposedly had no scruples against using whatever means were available to achieve his goals, who carried out “general massacre,” and who “took delight in enemies slain,” to exert such influence on world history that 1300 years after his death over three hundred million persons confess their faith in him? The witness of many centuries of history and the witness today of an Islam that is still vigorous refute more conclusively than any other argument the judgments that Ahrens expressed on the basis of a flawed interpretation.” Fueck further asserts that the concept of cyclical revelation is intrinsic to Muhammad’s prophetic consciousness: “This cyclical theory of revelation cannot be derived either from Judaism or from Christianity. The idea … seems to be Muhammad’s own creation. It reflects his philosophy of history and indicates how he understood his relationship to other peoples who had previously received a divine revelation. It is convincing evidence that Muhammad could not have received the decisive stimulus to prophetic action from either Jews or Christians.”

Biblical Stories

The presence in the Qur’an of many biblical stories is often cited as proof of Muhammad’s dependence upon Christian and Jewish sources. Yet this is false logic and there is no rational justification for this, for several reasons. First, the Qur’an itself has come to affirm the truth of previous scriptures and to correct that which has been corrupted. Second, and as any student of the Qur’an and the Bible would easily notice, the Qur’anic accounts contain many detailed and important differences as well as focusing on points of emphasis. The Qur’an focuses largely upon the lessons to be drawn, the glad tidings and warnings that are to be understood, the explanation of Islamic doctrines, and consolation of the Prophet through these stories: “All that We relate to thee of the stories of the messengers, with it We make firm thy heart: in them there cometh to thee the Truth, as well as an exhortation and a message of remembrance to those who believe” (11:120). Further, the Qur’an does not give a detailed account of all the previous prophets sent to mankind: “Of some messengers We have already told thee the story; of others we have not” (4:164), and of those prophets whose stories are mentioned, little historical detail is given concerning them. The Qur’an’s emphasis is upon the moral and spiritual lessons to be gained from these stories. One important point of difference is that the Qur’an makes no mention of the immoral behavior which the Bible attributes to several prophets including Jacob (Genesis 27), Lot (Genesis 19:30–38), David (II Samuel 11:1–27), and Solomon (I Kings 11:1–10). Rather, it vindicates them, purging their personality and character of the indecencies, obscenities, and myriad of moral and spiritual defects ascribed to them.

Purifying the Models

In the Qur’an they are not only presented as God’s prophets and messengers but as men of great character, infallible human beings who lived their lives as walking embodiments of submission to God’s will and commandments. Watt observes that “there is something original in the Qur’an’s use of the stories and in its selection of points for emphasis,” and to him “[i]ts originality consists in that it gave them greater precision and detail, presented them more forcefully and by its varying emphasis, made more or less coherent synthesis of them; above all, it gave them a focus in the person of Muhammad and his special vocation as messenger of God.” Additionally, biblical stories are used in the Qur’an as illustrative material, playing a subordinate role, to substantiate Qur’anic themes. Fueck observes: “it was the discovery of a substantive correspondence between his own preaching and what Christians and Jews found in their sacred books that first motivated him to concern himself more directly with their tradition, for it is the second Meccan period that first reflects an extensive knowledge of biblical stories.” Watt observes that, “There is no great difficulty in claiming that the precise form, the point and the ulterior significance of the stories came to Muhammad by revelation and not from the communications of his alleged informant.”

Radical Differences

In addition to this, if Muhammad had borrowed material from the Christians or Jews he could never have preached a faith so radically different from Christianity and Judaism. Moreover, given the hostile climate and antagonism that existed between Muhammad and his adversaries, and given that he lived in the full light of history with his life an open book and the subject of detailed and prolific research, the name of an alleged informant could scarcely have remained unknown to his enemies and contemporaries or non-existent down the centuries.

The Qur’an informs us that similar accusations of Muhammad having borrowed and learned from others were also leveled by the Makkan elite: “But the misbelievers say: “Naught is this but a lie which he has forged, and others have helped him at it.” In truth it is they who have put forward an iniquity and a falsehood. And they say: “Tales of the ancients, which he has caused to be written: and they are dictated to him morning and evening.” (25:4–5)

The Makkans would also mention certain individuals as Muhammad’s teachers, as the Qur’an states: “And we know well that they say: Only a man teaches him. The speech of him at whom they falsely hint is outlandish and this is manifest Arabic speech” (16:103). Several reports concerning the alleged teachers of the Prophet exist. One of them names the person as Jabr, a Roman slave of Amir ibn al- Hadrami, another mentions A’ish or Ya’ish, a slave of Huwaytib ibn Abd al-Uzza, and yet another points to Yasar, a Jew, whose agnomen (kunyah) was Abu Fukayhah, and who was the slave of a Makkan woman. Still another report mentions someone by the name of Bal’an or Bal’am, a Roman slave. Rather like grasping at straws any acquaintance of Muhammad who had the slightest knowledge of the Torah or Gospels was touted as the alleged teacher of the Prophet. The Qur’an refuted these allegations by arguing that the individuals being pointed to were non-native Arabs with minimal language skills while the Qur’an was an Arabic composition of the highest linguistic standards. The evidence therefore spoke for itself.

Today little has changed, with the same accusations still being leveled by writers such as Gardner and others, in this instance naming Salman, a Persian convert, as the chief aid of the Prophet in composing the Qur’an. However, in reality, Salman only met the Prophet in Madinah, and as mentioned earlier, the greater part of the Qur’an was revealed in Makkah with most of the stories in question revealed in the later part of the Makkan period. So, given historical facts, the Prophet could not have learned the stories from Salman. Moreover, Salman was a devoted follower of the Prophet, a reality that would categorically not have been the case were either he or any other person for that matter, to have been teaching Muhammad behind the scenes. Consequently, any attempt to prove Muhammad’s dependence upon Jewish or Christian sources argues Fueck, “leads inevitably to insoluble difficulties and contradictions.” Muslim explanation of the similarities that exist between the biblical and Qur’anic accounts is clear: a) the source of both scriptures is one, Almighty God, b) the Qur’an came to affirm the truth of previous scriptures c) it came as a corrective force to realign mankind to the straight path where deviation had occurred through tampering with earlier revelation and biblical narrations (whether through changes, insertions or deletions). So, Muslims consider similarities neither unusual nor impossible for they form a universal norm that stands for all time.

Therefore, Watt’s contention that the form and significance of the biblical stories in the Qur'an likely came to Prophet Muhammad through revelation rather than from external sources is correct. If Prophet Muhammad had borrowed from Jewish or Christian sources, it would be unlikely for him to preach a faith so distinct from these religions. Given the scrutiny and opposition he faced, the identity of any supposed informant would not have remained hidden.

Patricia Crone and Micheal Cook

Wansbrough's contention that the Qur'an is a post-Prophet Muhammad compilation, emerging from the stabilization of political power in the second/eighth century, is ahistorical and unsubstantiated.

Patricia Crone and Michael Cook espouse the same theory in their controversial work Hagarism. Without any further inquiry or questioning of premises they confess their indebtedness to Wansbrough for their views on the Qur’an concluding that, “There is no hard evidence for the existence of the Koran in any way before the last decade of the seventh century, and the tradition which places this rather opaque revelation in its historical context is not attested before the middle of the eighth.” Apparently, they would seem to deny the historical existence of Muhammad even, taking both the Qur’an and the entire corpus of Islamic teachings to be simply a conspiracy and fabrication of mysterious “Hagarenes” who supposedly invented their prophet: “Where the Hagarenes had to fend for themselves was in composing an actual sacred book for their prophet, less alien than that of Moses and more real than that of Abraham. No early source sheds any direct light on the questions how and when this was accomplished. With regard to the manner of composition, there is some reason to suppose that the Qur’an was put together out of a plurality of earlier Hagarene religious works. In the first place, this early plurality is attested in a number of ways. On the Islamic side, the Koran itself gives obscure indications that the integrity of the scripture was problematic, and with this we may compare the allegation against Uthman that the Koran had many books of which he had left only one. On the Christian side, the monk of Bet Hale distinguishes pointedly between the Koran and the surat al- baqara as source of law, while Levond has the emperor Leo describe how Hajjaj destroyed the old Hagarene ‘writings’.”

Crone and Cook further assert that the literary character of the Koran, its obscurity of meanings, lack of structure and repetition of whole passages leads one plausibly to argue that “the book is the product of the belated and imperfect editing of materials from a plurality of traditions. At the same time the imperfection of the editing suggests that the emergence of the Koran must have been a sudden, not to say hurried, event.” And they go on to conclude that this conspiracy took place at the time of Hajjaj (by the end of the seventh century): “It is thus not unlikely that we have here the historical context in which the Koran was first put together as Muhammad’s scripture.”

Nonsensical Theory

This theory is so nonsensical and historically unsubstantiated that Christian, Jewish and Islamic scholars have rejected it altogether. In his review of Wansbrough’s Qur’anic Studies, Serjeant dismissively states that “An historical circumstance so public [as the emergence of the Qur’an] cannot have been invented.” He further observes that John Burton “argues vastly more cogently than Wansbrough’s unsubstantiable assertions, that the consonantal text of the Qur’an before us is the Prophet’s own recension.” N. Daniel reviewing Hagarism, writes: “The notion that a “conspiracy” is involved in such a historical reconstruction becomes a rallying point for many objections.” Andrew Rippin, on the other hand, defends the theory, arguing: “one hundred years is a long time, especially when one is dealing not with newspaper headlines and printing presses but the gradual emergence of a text at first within a select circle, then into ever-widening circles. One could point to similar instances of “conspiracies” in the canonization of the other scriptures, for example, the identification of John the Disciple with the Gospel of John is well less than a century after the emergence of the text. There is a huge difference between a plausible conjecture and a historical reality.

Rippin still has to substantiate his claim that the same real “conspiracy” that attributed the pseudo-Gospel to Jesus’ disciple “John” took place in connection with the Qur’an also.

Fazlur Rahman observes that there are several problems with Wansbrough’s thesis. Consider first Wansbrough’s second thesis, that the Qur’an is a composite of several traditions and hence post- Prophetic: “I feel that there is a distinct lack of historical data on the origin, character, evaluation, and personalities involved in these “traditions.” Moreover, on a number of key issues the Qur’an can be understood only in terms of chronological and developmental unfolding within a single document.” He further argues that “Wansbrough’s method makes nonsense of the Qur’an, and he washes his hands of the responsibility of explaining how that “nonsense” came about.” Fazlur Rahman declares these methods as “so inherently arbitrary that they sink into the marsh of utter subjectivity.”

R. W. Bulliet

We conclude the discussion with Columbia professor R. W. Bulliet’s statement in his important work Islam, The View from the Edge: “I cannot imagine how so abundant and cohesive a religious tradition as that of the first century of Islam could have come into being without a substantial base in actual historical event. Concocting, coordinating, and sustaining a fantasy, to wit, that Muhammad either did not exist or lived an entirely different sort of life than that traditionally depicted, and inculcating it consistently and without demur among a largely illiterate community of Muslims dispersed from the Pyrenees to the Indus River would have required a conspiracy of monumental proportion. It would have required universal agreement among believers who came to differ violently on issues of far less import.”

Bulliet identifies certain radical Shiite groups who argue that the early caliphs deliberately excluded two chapters from the Qur’an. These chapters allegedly highlighted the virtues of the Prophet Muhammad's family (Ahl al-bayt) and their inherent right to govern, with specific emphasis on Caliph Ali's unique qualifications. Furthermore, these groups maintain that Caliph Ali had a distinct version of the Qur’anic text, which differed from the versions compiled by Caliphs Abu Bakr and Uthman. Nevertheless, these reckless, clearly politically motivated, claims of falsification in the Qur’anic text have been roundly rejected by both Sunnis as well as mainstream Shiite scholars. Reaching the same conclusions as mainstream Muslims they have also been dismissed by several oriental scholars having thoroughly examined the issue. Gatje writes that “Such accusations, which are tantamount to alleging a conscious falsification to the determent of Ali and his successors, do not stand up under investigation. On the contrary, a so-called ‘Sura of Light’, which has been handed down outside the Qur’an, represents with certainty a Shi’ite falsification.” Burton notes that “Ali succeeded Uthman and if he had any reservation about the Qur’an text, he could easily have reinstated what he regarded as the authentic revelation.” Muir denounces these accusations as “incredible”. Giving several reasons to reject these accusations he writes: “At the time of the recension, there were still multitudes alive who had the Coran, as originally delivered, by heart; and of the supposed passages favoring Ali – had any ever existed – there would have been numerous transcripts in the hands of his family and followers. Both of these sources must have proved an effectual check upon any attempt at suppression.” He further argues: “The party of Ali shortly after assumed an independent attitude, and he himself succeeded to the Caliphate. Is it conceivable that either Ali, or his party, when thus arrived at power, would have tolerated a mutilated Coran – mutilated expressly to destroy his claims? Yet we find that they used the same Coran as their opponents, and raised no shadow of an objection against it.” Muir concludes that “Such a supposition, palpably absurd at the time, is altogether an after-thought of the modern Sheeas.”

A Miracle

According to orthodox Muslims, the preservation of the Qur’anic text in such an authentic fashion is no less than a miracle of Allah, a lasting miracle. Indeed, the Qur’an itself in its very early Makkan period cites Allah’s promise to protect it: “We have, without doubt, sent down the Message and We will assuredly guard it [from corruption]” (15:9). Owing to the divine guarantee and the Qur’an’s extraordinary and unparalleled character (‘ijaz), no one, not even the extreme Shiite sects referenced, has succeeded in altering its content. This careful preservation of the Qur’an is a historically verified and widely acknowledged truth. So much so that the Shiites, observes Lammens, have “not dared to introduce these restitutions into Qorans which the sect uses for liturgical ceremonies and which agree with the edition transmitted by the Sunni channel.” Consequently, there has only ever been one text of the Qur’an in the hands of both Sunni and Shiite Muslims, this universally recognized text enjoying normative authority for both. David Pinault a modern scholar on Shiism observes: “In Sunnism and Shiism alike the Qur’an enjoys an authority not fully comparable with that of the Bible in Judaism and Christianity. The latter religions ascribe the Bible to human authors (albeit divinely inspired) and consider the component texts comprising Scripture to be the product of human history, the records of the Creator’s interaction with His people. From a Muslim perspective the author of the Qur’an is not Muhammad nor any other human but rather God Himself...”

Esteemed George Town scholar S. Hossein Nasr, who himself happens to be a Shiite, puts the point in a nutshell: “There is only one text accepted by all Muslims, Sunnis and Shi’ites and other branches of Islam alike, and it is this definitive book which stands as the central source of truth, guidance and of inspiration for all Muslims.”

The question of the integrity of the Qur’anic text so easily raised out of thin air by the authors of Hagarism is not surprisingly unsubstantiated. What we are in fact left with is a simple repetition of earlier medieval stereotypes which should have been laid to rest a long time ago as products of an age of ignorance. I refer specifically to the “dove” and “bull” stories and claims of Pedro de Alfonso as well as others who alleged that the existing Qur’an did not really represent what the Prophet originally claimed. It is a universally recognized, historical fact that the unity, integrity, and absolute textual uniformity of the Qur’an has been maintained since its compilation into a single volume and text, and to challenge this fact is to leap into the realm of the absurd. Wild theorizing has no place where facts are indisputable. There has only ever been one same Qur’anic text in the entire world. W. Muir, recognizing the purity of the Uthmanic text, asserted: “The recension of Uthman had been handed down to us unaltered. So carefully, indeed, has it been preserved, that there are no variations of importance – we might almost say no variations at all – among the innumerable copies of the Coran scattered throughout the vast bounds of the empire of Islam. Contending and embittered factions, taking their rise in the murder of Uthman himself within a quarter of a century from the death of Mahomet, have ever since rent the Mahometan world. Yet but ONE CORAN has been current amongst them; and the consentaneous use by them all in every age up to the present day of the same scripture is an irrefragable proof that we have now before us the very text prepared by command of the unfortunate Caliph. There is probably in the world no other work which has remained twelve centuries with so pure a text.”

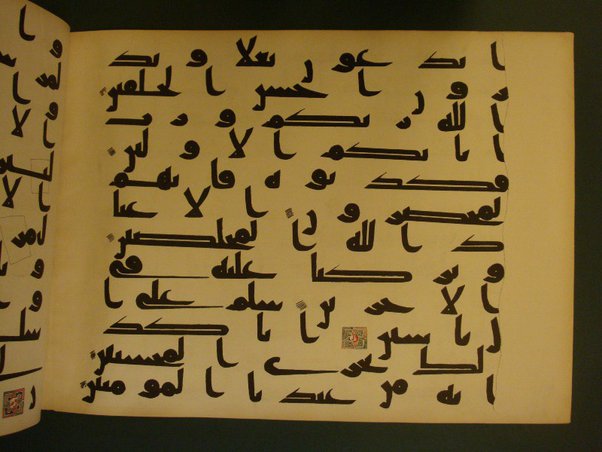

John Burton

John Burton concludes his book with the following words: “only one text of the Qur’an has ever existed. This is the universally acknowledged text on the basis of which alone the prayer of the Muslim can be valid. A single text has thus already always united the Muslims....What we have today in our hands is the mushaf of Muhammad.” H. Lammen’s suggests: “The Qoran, as it has come down to us, should be considered as the authentic and personal work of Muhammad. This attribution cannot be seriously questioned and is practically admitted, even by those Muhammaden sects who obstinately dispute the integrity of the text; for all the dissidents, without exception, use only the text accepted by the orthodox.” The discovery of Sana'a Manuscripts substantiate Burton's points and negate John Wansbrough's untenable speculations.

Related Articles

The emergence of Islam in the 7th century CE with a distinct, democratically oriented, consultative governmental structure

Dr. Zulfiqar Ali Shah, Even though the central pivot of all New Testament writings is Jesus Christ and crucial information...

Gaza City, home to over 2.2 million residents, has become a ghostly emblem of devastation and violence

Gaza City, a sprawling city of over 2.2 million people is now a spectral vestige of horrors

The Holy Bible, a sacred text revered by Jews and Christians alike, has undergone centuries of acceptance as the verbatim Word of God

Tamar, the only daughter of King David was raped by her half-brother. King David was at a loss to protect or give her much-needed justice. This is a biblical tale of complex turns and twists and leaves many questions unanswered.

There is no conflict between reason and revelation in Islam.

The Bible is considered holy by many and X-rated by others. It is a mixture of facts and fiction, some of them quite sexually violent and promiscuous. The irony is that these hedonistic passages are presented as the word of God verbatim with serious moral implications.